Villa's inability to pay for the desperately needed munitions for the Division of the North created an opening for German agents to support both sides in Mexico's civil war and thus extend it. Sommerfeld, Pancho Villa's chief arms supplier in the U.S. and German naval intelligence agent, began shipping on a $420,000 contract on April 1, 1915 for 12 million 7mm cartridges. This contract was with the Western Cartridge Company in Alton, Illinois. Sommerfeld had made this deal on behalf of Villa in February 1915. The Mexican general had provided a down-payment of $50,000. For this order only the initial deposit appears in the accounts of Lázaro De La Garza, who had financial control of all New York funds of Villa’s supply chain. This leads to the unanswered question, who paid for the balance of this contract? The entire order was produced, paid for, and shipped to Villa between April and August 1915. The price per thousand cartridges was an astonishingly low $35, while Remington and Winchester charged $50 for the same product, and Peters Cartridge Company between $55 and $60.

The standard Mexican 7mm Mauser cartridge of 1915

Sommerfeld closed another arms contract on May 14, 1915, this time for 15 million cartridges at the same price as his earlier contract, $35 per thousand, valued at $525,000 ($11 Million in today’s value). There are several astonishing aspects to Sommerfeld’s deal. First, the price Sommerfeld got for the munitions was, again, at least thirty percent below market value. How did he get such an outstanding deal? Second, he managed to occupy the entire capacity of Franklin W. Olin’s Western Cartridge Company factory in East Alton for the year 1915 with this second order. Sommerfeld was now on the hook for $945,000 ($20 Million in today’s value), as Villa’s fortunes declined, and the Villista fiat money was rapidly losing value. The German agent expected to make 2% commissions, $18,900 if both contracts were fulfilled ($400,000 in today’s value). All the while he managed these huge contracts as a German in the middle of a huge spy scare that had gripped the United States as a result of the German sabotage campaign against U.S. targets.

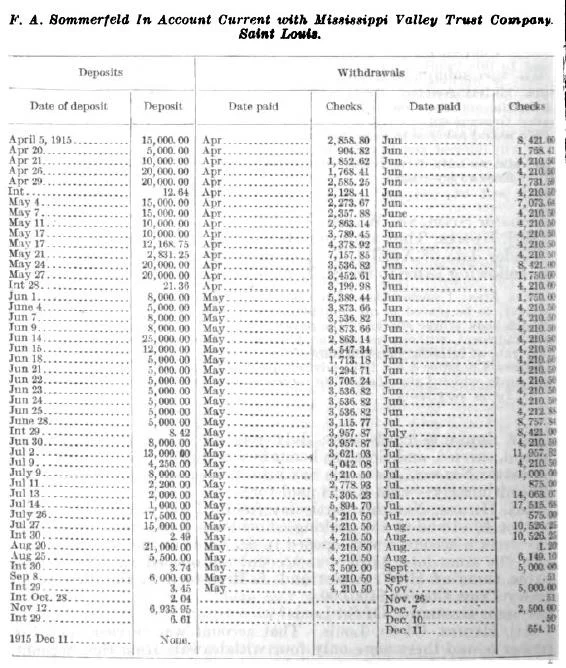

Sommerfeld’s account at the Mississippi Valley Trust Company shows a total $381,000 flowing through it from April to December 1915.

Only days after closing on the second contract for the fifteen million cartridges, on May 17, 1915, he signed the contract over to Lázaro De La Garza. De La Garza provided the down-payment of $65,000, which went to the Western Cartridge Company. The money came from Francisco Madero's uncles Alberto, Alfonso and Ernesto in New York, probably profits from sales of goods from the area Villa controlled in Northern Mexico, such as bullion, cattle, rubber, or cotton. De La Garza also logged a deposit “en B[an]co St. Louis” in May for $30,000. This amount does not show up on Sommerfeld’s account.

The head of the Secret War Council, Heinrich F. Albert, withdrew that exact amount in May from his account at the St. Louis Union Bank. Obviously, not just Albert, but also Sommerfeld maintained accounts St. Louis and specifically in the St. Louis Union Bank. This account was connected with Albert's. Assuming that Sommerfeld paid for both contracts, his St. Louis Union Bank account showed transactions of roughly $400,000, similar to another account he maintained at the Mississippi Valley Trust account. Only $145,000 of the total $945,000 appeared in the books of De La Garza. The French government ended up buying $265,000 worth later in 1915. The Carranza faction took $150,000 of the munitions in September. The Western Cartridge Company refunded $65,000. This leaves $385,000, almost the exact sum of Sommerfeld’s Mississippi Valley Trust transactions and what the U.S. government alleged to have come from Heinrich Albert ($381,000). The $385,000 also matches the funds believed to have remained on Albert’s various accounts in Milwaukee, Cleveland, St. Louis, and Chicago.

Another question looms large as well: Why would Franklin W. Olin sell munitions to Sommerfeld thirty percent or more below market value? Even if Olin would have sympathized with the German cause to the point that he refused to produce munitions for the Entente, he still could have commanded a higher price from the various Mexican factions, even Villa’s. Incidentally, De La Garza’s accounts show payments to Peters Cartridge Company for the same type of ammunition in May 1915 priced at $55 per thousand. The answer to this riddle may have revealed itself in the spring of 1916 when, out of the blue, and, without much fanfare, F. W. Olin opened a brass casing factory next to Western Cartridge Company in Alton, Illinois.

Olin was a businessman who believed in vertical integration. He started his business in 1892 when he founded the Equitable Powder Manufacturing Company. The company’s blasting caps served mostly the coal industry in the Midwest. He expanded the production to include small arms ammunition in 1898, changing the name to Western Cartridge Company. He also founded a company that manufactured targets in the same year to better serve his sporting and hunting rifle customers. The Western Cartridge Company had managed to carve out a nice slice of the U.S. munitions market dominated by the large arms manufacturers such as Winchester Rifle Company and Remington by the early teens. Since the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 the company thrived. The success resulted from the fact that Western was willing to produce 7mm Mauser cartridges widely used in Mexico. The Western Cartridge Company had sold millions of cases of ammunition through Sommerfeld to Madero, Carranza, and Villa over the years.

President Franklin Olin and his son, John, liked doing business with Sommerfeld. His clout over the past years had made the transportation of shipments across the international border smooth. When the U.S. government instituted various embargos, Sommerfeld called on his friends in very high places, such as Lindley Garrison, Secretary of War, or William Jennings Bryan, Secretary of State, or Hugh Lenox Scott, the General in charge of border troops and later President Wilson’s Chief of Staff of the Army and received permission to export. Sommerfeld also stood by his word. He was very well organized, understood proper specification, had the customer contacts, and, most importantly, he always paid on time.

The savvy businessman chomped at the bit when Sommerfeld asked Olin to quote on the two largest munitions orders in the company’s history. An order of that size would allow Olin to install his own brass mill to produce the cartridge cups. However, where to get the all-important presses for such a production? Enter Carl Heynen and the Bridgeport Projectile Company. Heynen was a German naval intelligence agent and ran the sham munitions plant for his German superiors. Using the Bridgeport Projectile Company as a front, Heinrich Albert had signed contracts in the spring of 1915, locking up the entire capacity for smokeless powder and for hydraulic presses in the United States. Where did Olin get this equipment that allowed him to open a brass mill in the spring of 1916? The difference between the sales price and market price on twenty seven million cartridges that Sommerfeld contracted amounted to approximately $405,000 ($8.5 million in today’s value). Heynen accounted for the cost of hydraulic presses he had ordered and which were actually produced: “$417,550 for presses which had actually been produced.” A striking coincidence! If true, the German government supported Olin’s plans for a brass mill with the understanding that he would not produce for the Entente; hence, the contracts with Sommerfeld at a price far below market value. The new factory would prove to be a boon for Olin. He came out of the war with tremendous financial strength. In 1931 he bought Winchester. Olin Industries is one of the largest corporations in the United States to this day, partly thanks to Franklin Olin and the connections of his good friend, Felix A. Sommerfeld.

This blog series will trace the events that led to Villa's attack on Columbus, New Mexico on March 9, 1916 in weekly segments. On March 12, I will speak at Columbus for the Centennial Commemoration of the raid and reveal how Villa was made to believe that attacking the United States was a good idea. If you get impatient and do not want to wait for eight months to learn the facts behind Columbus, buy Felix A. Sommerfeld and the Mexican Front in the Great War now.