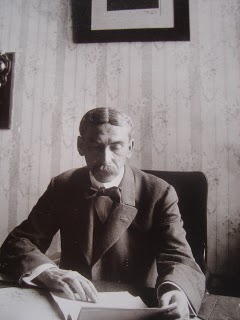

In November of 1913 Felix Sommerfeld made the acquaintance of a special envoy and friend of President Woodrow Wilson: William Bayard Hale. Born in 1869, Hale studied at Boston and Harvard

universities. He graduated from Episcopal Seminary College in Cambridge. He

began his career as an ordained priest in Boston in 1893. In 1900 the then

thirty-one-year-old Hale decided to become a journalist. As a first job, the

retired clergyman signed on as managing editor of the Cosmopolitan Magazine.

After three years he switched to the Philadelphia Public Ledger and ran the

editorial board until 1906, when the New York Times hired him as foreign

correspondent for Paris, France. In

1908, Hale also wrote for the New York American, a Hearst paper, as its Berlin

correspondent. Widely acclaimed for his thoughtful political analysis, the

journalist and author interviewed the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II. This interview was

according to some the most insightful ever with the German monarch. The

following year, 1909, Hale married Olga Unger, a German-American in London. As

a personal friend and adviser of then governor of New Jersey, Hale wrote and

published Woodrow Wilson’s biography in 1911. He played a major role in the

highly contested presidential election campaign of 1912. As Wilson’s friend and

confidante Hale went on sensitive diplomatic

missions in 1913 and 1914 concerning the Mexican Revolution and upheavals in Central America. The first such mission resulted in the dismissal of

the notorious American ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson. Sommerfeld had

organized meetings between Hale and the First Chief of the Constitutionalists

in Mexico, Venustiano Carranza.

According to Sommerfeld’s testimony in 1918, Dr. Hale had a hard time

negotiating with Carranza in the fall of 1913. To begin with the First

Chief refused to see Wilson’s emissary since Hale did not have official

government credentials. Always a stickler for process, Carranza wanted to force Wilson into a de-facto

recognition that mandated a diplomatic representative to be dispatched to

him. Naturally, not lacking a measure of

pigheadedness himself, Wilson did not accept. To prevent the issue from coming

to a head, the Wilson administration relied on Felix Sommerfeld in November 1913

to intercede with Carranza. “While in Sonora Mr. William Hale came there and we went to the border

and arranged a meeting between Carranza and Hale and acted as a go-between.”

It took Sommerfeld from November 2 until November 12, 1913 to get Carranza to grant the audience. However, Sommerfeld’s job had just started. Carranza refused to discuss anything that, in his

opinion, touched upon affairs of a domestic nature. At issue was President

Wilson’s attempt to somehow arrive at a compromise

government for Mexico that would be able to allow for and set up national

elections. Of course, by November the Constitutionalists had just won several

major battles and had no interest in compromise. The talks quickly stalled.

According to historian Cumberland, Hale threatened U.S. intervention and

Carranza retorted with the threat of war. Sommerfeld recalled, “…they [Hale and

Carranza] were always sparring

around and after the meetings I would go and talk to Carranza.”

The efforts of the German agent came to nothing. Hale and Carranza split in a huff. The First Chief’s mode of

operation, being dilatory, delegating, and insisting on written communication,

directly contradicted Hale’s “go-getter” energy. Sommerfeld tried again to bridge the gap. At the

urging of Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, the German agent rushed to Tucson, Arizona on November 10th 1913,

where Hale waited in vain to be received by Carranza. “I came back because I heard that Dr.

Hale had left Carranza in disgust or anger. I met Dr. Hale in Arizona

and told him not to lose his patience because Carranza was stubborn and wouldn't let the United

States interfere in Mexican politics. He wouldn't discuss politics with Dr.

Hale. I told him ‘sit still, I am going down to see him.’…I tried to coax him

to come off the high horse. He wouldn't …

The problems Hale faced in relating to the

First Chief were symptomatic for many who had dealings with the stubborn

politician from Coahuila. In part because of his failed attempts to broker an

agreement between Hale and Carranza, Sommerfeld realized that he as well could not

get along with Carranza. It is unclear whether, as Sommerfeld

recounted, Carranza asked him

to work with Pancho Villa, or whether Sommerfeld was fired as a result of the Hale

intervention. However, around Christmas 1913, Sommerfeld switched from the

Carranza to the

Villa camp. From that moment on Carranza is not

known to have ever again personally interacted with Sommerfeld. Historical

sources after December 1913 show only lawyer and lobbyist Sherburne G. Hopkins officially working for Carranza. One other fact, however, became painfully

apparent: The American embassy in Mexico City as well as the Latin American

desk in the State Department in 1913 and beyond had lost their roles as policy

advisers of the American President.

Sommerfeld would again work with the American journalist in 1914. After a disagreement with the President, Hale was looking for a job. Sommerfeld, always a keen observer and strategist recommended his friend to Bernhard Dernburg who was then heading the German propaganda effort in the US. Hale was hired to "fix" the dilettantism of German efforts. In 1917, William Randolph Hearst sent him to Europe as a war correspondent. Largely discredited and shunned as a traitor, Hale spent most of the time after the war until his death in 1924 in Europe.