In the Battle of Ojinaga in December 1913 a famous American writer disappeared without a trace. Ambrose Bierce, who wrote the last known letter to his daughter Helen on December 26th 1913 from Chihuahua City, had been seen as an active participant in the Battle of Ojinaga. “He said that he had ridden four miles to mail the letter and that he had been given a sombrero as a reward for ‘picking off’ one of the enemy with a rifle at long range. He also told her that he was leaving with the army for Ojinaga, a city under siege, the following day.” After the battle he disappeared and no trace of him was ever found. Bierce’s daughter Helen became alarmed after she had not heard anything of her father by January. Most disturbing was the appearance that Bierce had arranged his affairs at home in a way that pointed to his expectation not to return. The seventy-one-year-old writer had been suffering from depression. In a letter to his cousin Laura, Bierce wrote on December 16th 1913: “Good-bye — if you hear of my being stood up against a Mexican stone wall and shot to rags please know that I think that a pretty good way to depart this life. It beats old age, disease, or falling down the cellar stairs. To be a Gringo in Mexico — ah, that is euthanasia!"

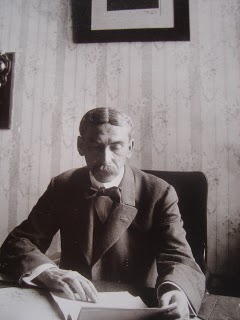

Bierce's letter to a friend saying "Good Bye"

Helen approached the U.S. government to help find her father. Apparently, and quite different from the timeline most historians offer on the efforts of the U.S. government to find Bierce, the request was not made until September 1914. General Scott related the message from Secretary of the Interior, Franklin Lane, to Felix Sommerfeld.

“The Secretary of the Interior, Mr. Franklin K. Lane, is very anxious to get news of a man by the name of Ambrose Bierce, who went to Mexico last year and his friends have heard nothing from him since last December. He is quite a poet and writer, was 71 years of age when he left Washington last fall, was feeling exceedingly strong and healthfull [sic]…He…was accredited to the Villa forces…He had a considerable sum of money with him…In this letter [dated 12-26-1913] he said that his subsequent addresses would be indefinite, that he intended to go [on] horseback and by rail, when possible, through to the West coast of Mexico and from thence to South America…The Secretary would like you to have confidential inquiry made to trace Mr. Bierce. Anything you can do in this direction will be greatly appreciated by him and by the Secretary of War.”

The German agent tracked Bierce from El Paso to Chihuahua City where the writer’s presence had been confirmed and the last letter was sent from on December 26th. In this letter Bierce claimed that he was leaving on a troop train from Chihuahua to Ojinaga. The time frame coincides exactly with the dispatch of six brigades under Generals Ortega and Natera to Ojinaga. Of course, the generally accepted story that Bierce somehow attached himself to Villa is untrue given this time frame. Very surprising is the fact that Bierce did not join the movie producers, journalists, and other foreign admirers of Pancho Villa to witness this last battle for control of Chihuahua. At least, none of those remembered Bierce after his disappearance. Tex O’Reilly, the soldier-of-fortune turned writer was one of the few people who claimed to have heard of Bierce coming through El Paso and on to Chihuahua City. “O'Reilly says that several months later, he heard that an American had been killed in a nearby mining camp of Sierra Mojada. He investigated and heard how an old American, speaking broken Spanish, was executed by Federal Troops when they found out he was searching for Villa's troops. The locals told how he kept laughing, even after the first volley of his execution.” Since not many of Tex’ stories pass the truth test, it is likely that O’Reilly simply related rumors as his own research.

The most widely accepted stories placed Bierce in Ojinaga in the beginning of January. There, the course of events separate. Some rumors had it that the “old gringo” got in a fight with Pancho Villa and was executed. “Odo B. Slade, a former member of Pancho Villa’s staff, recalled an elderly American with gray hair and an asthmatic condition who served as a military advisor to Villa. The American was called Jack Robinson, and he criticized the Mexicans’ battle strategies with the accomplished eye of a military expert.” Another claimed that Bierce got lost on the battlefield and was captured by federals that killed him. A more conservative and perhaps more realistic twist was that Bierce “…started out to fight battles and shoulder hardships as he had done when a boy, somehow believing that a tough spirit would carry him through. Wounded or stricken with disease, he probably lay down in some pesthouse [sic] of a hospital, or in some troop train filled with other stricken men. Or he may have crawled off to some waterhole and died, with nothing more articulate than the winds and the stars for witnesses.” George Weeks, a friend of Bierce, traveled to Mexico in 1919 to research the author’s disappearance. According to an officer of the Mexican army, Bierce “had collapsed during the attack on Ojinaga and had died from hardship and exposure.”

Sommerfeld’s research revealed a potentially different chain of events: Bierce probably never was in Ojinaga or survived the battle and returned to Chihuahua City right after the battle. Sommerfeld found out that the writer left Chihuahua City to the south not to the north where Ojinaga is located. “I investigated in Chihuahua, Mexico and found out that Mr. Bierce left that City some time [sic] in January 1914 for the South, and that is the last anybody [had] ever seen or heard of him. I communicated that information at that time to General Scott on my return to Washington.” Bierce leaving to the south solves several inconsistencies: Villa, who Bierce claimed to have been with, was in Chihuahua City in the beginning of January and had had no plans to come to Ojinaga. If Bierce was with Villa and stayed with him through the battle, why did neither Villa nor anyone else in the Villa camp remember seeing him? If Bierce traveled south towards Durango, he was executing his plan of trying to make it to Mexico’s west coast. If he wanted to see fighting, there was plenty of action in January of 1914 in the Laguna region. Also important was the fact that in order to go west, one had to come through Torreon, the railroad hub in central Mexico.

Carey McWilliams, a journalist and Bierce’s biographer, seemed to share Sommerfeld’s conclusion that the famous writer was alive after the Battle of Ojinaga. Through the good offices of Sherburne Hopkins, McWilliams addressed a letter to Sommerfeld in April 1930 in which he asked for any information about “an ammunition train that was supposed to have been captured by Gen. [Rudolfo L.] Gallegos in the state of Durango in February 1914? It had been rumored that Bierce was attached to this train which was destined for the Huerta forces in Torreon.” Sommerfeld could not offer McWilliams much additional information. The only leads he could provide to the journalist were to check with the Arrieta brothers who were in charge of the Constitutionalist forces in the Laguna and around Torreon in 1914.

The matter of Bierce carrying “a large sum of money” has not been mentioned in the historiography of his disappearance. The Mexican countryside in the early days of 1914 was notoriously infested with rebels of any shape and form, deserted bands of federal soldiers, hapless and homeless peons, and bandits. An old “gringo” traveling with guides, or on a train that had been captured, would have been a prime target for robbery or worse. Conceivably, he was robbed and dumped somewhere along the way without any witnesses. The true story might never see the light of history. Sommerfeld explained the reason why he did not search further for Bierce in 1914. “When I received the letter from General Scott, it was impossible to make any inquiries in the South as I was with the Villa faction and the South was in the hands of the Carranza partisans.” Sommerfeld felt that he satisfied his obligations to General Scott and his superiors in the Wilson administration. Clearly, he did not obsess over the vanished poet. Sommerfeld had more important things to do in the final push against Huerta than to research the disappearance of a suicidal writer in the middle of a war. In a strange twist of history, Sommerfeld’s response to Carey McWilliams in May of 1930 from the Hotel Bristol in Berlin is the last known correspondence of the German agent. Just as is the case with Ambrose Bierce, when, where, and how Sommerfeld died remains a under a veil of secrecy that no historian has lifted to this day.