Two detachments of Villistas, amounting to an estimated 485 men under the command of Candelario Cervantes and the infamous Pablo López, simultaneously attacked the cavalry camp and the town at 4:11 am on March 9, 1916. Villa himself likely stayed behind in Mexico with a small reserve. The raiders stormed into town shooting up the bank, and set fire to the Commercial Hotel, where they executed its manager W. T. Ritchie, as well as several overnight guests. The raiders proceeded to loot the town and fired indiscriminately at homes, where unsuspecting residents were sleeping. A detachment of Villistas sought to find and murder Sam Ravel. The owner of a local hardware store located in the same building as the hotel had allegedly cheated Villa sometime in the past. They looted the store. Ravel lived to see another day because he was out of town that night. However, insurance refused to cover his losses of $10,000 [$210,000 in today’s value], a heavy blow for the businessman. Simultaneously, the raiders attacked Camp Furlong.

This cartoon was in the papers of the German spymaster Heinrich F. Albert. It shows the glee with which Germany viewed the unfolding events in Mexico.

Luckily for the surprised cavalry soldiers, the raiders mistook the stables for the barracks and shot horses instead of men. The American soldiers mounted a counter-attack within a short time, forcing the Villistas into retreat. Twenty-three Villistas died during intense fighting. The raiding party withdrew into Mexico by 7:30 in the morning. Major Frank Tompkins chased the Villistas across the border with a squadron of fifty men and pursued them for five miles on Mexican territory. The Americans inflicted serious casualties on the rear guard of Villa’s forces. There are no exact numbers of losses on the Villista side, but Major Tompkins reported seventy-five killed. The 13th Cavalry lost one man and two horses. Tompkins himself had to abandon his horse and “was shot through the hat.” Short of ammunition, without supplies for the horses, and to “get something to eat,” he returned to Columbus later that day.

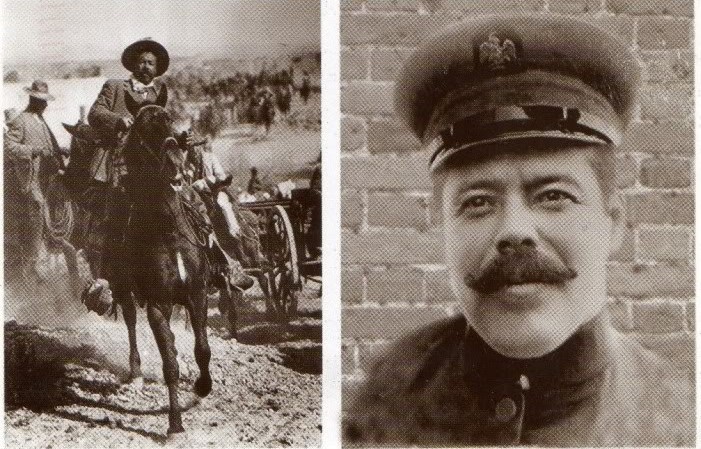

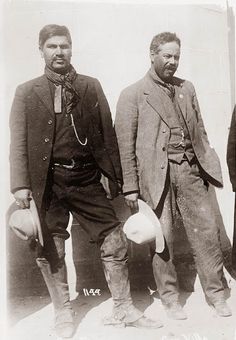

Images from the $5,000 reward wanted poster

The town was in shambles. Nine civilians and eight U.S. soldiers had died. Another nine soldiers had been injured; one of them succumbed to his wounds later. The authorities apprehended thirty raiders. George Seese and his companion who had stayed in the Commercial Hotel made it out alive but sufficiently shaken. Seese, who believed that he might have caused this mess, and who had a warrant pending for his arrest for polygamy, fled to Canada. He finally gave interviews to American investigators when he turned up in New York a few months later. He had nothing to add other than he really believed he could have taken Villa to President Wilson. No one asked him about Sommerfeld.

March 9 was the first day on the job for Secretary of War Newton K. Baker in Washington. He immediately ordered his predecessor, Hugh Lenox Scott, to mount a punitive campaign. General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing would be in charge. The mission was to pursue “the Mexican band which attacked the town of Columbus, New Mexico, and the troops there on the morning of the ninth instant.” Much to the glee of the Secret War Council, the so-called Punitive Expedition would tie up a significant majority of the American military at the Mexican border and inside Mexico for the next nine months. It seemed virtually assured at the time that it would be only a matter of time when Carranza’s forces would clash with American troops. A war between the United States and Mexico was expected in all quarters of the German and American governments when the situation became aggravated as a result of clashes with the U.S. military in May and June, 1916. The new American Secretary of War immediately ordered to look into expanding and equipping the military, forced to do what his predecessor could not implement and over which he resigned. The Columbus affair was a dream-come-true for the German military.

Countless books and articles since the attack speculated as to Villa’s motivations, his finances, and his backers. The revolutionary himself never commented on his attack. Why did he choose Columbus, New Mexico, a relatively unimportant town with little to loot and lots of military presence? The theories focused on Sam Ravel and Villa’s attack as an act of revenge. However, killing a merchant did not require a major military attack. There were plenty of Villista agents who could have meted out the punishment. Another school of thought was that Villa indeed wanted to cross into the U.S. to justify himself. The theory argues that when the plan fell apart, Villa lost control over his forces. Hugh Lenox Scott promoted this idea. However, Villa was no fool. He would have been arrested immediately for the murders of Americans in the preceding months. Many theories vaguely reference German agents as being behind Villa’s attack. A German physician from El Paso, Dr. Lyman B. Rauschbaum, had been close to Villa in 1915 and 1916. There is no evidence that he did anything other than stay close to Villa.

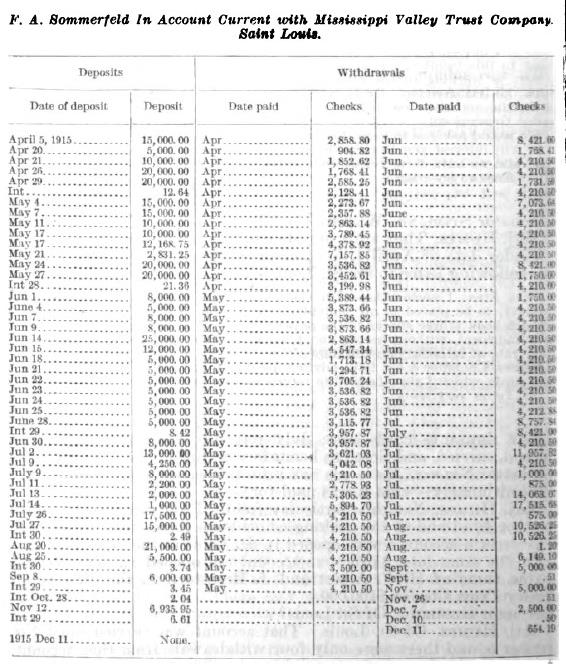

Suspicions also surrounded Felix Sommerfeld. It took some prodding from the editor of the Providence Journal and Carrancista representatives to get the B.I. to investigate Sommerfeld’s whereabouts. Special Agent J. W. Allen asked the Military Intelligence Division on March 14, 1916, to “inform the secret service and get them to shadow him and secure his effects for incriminating evidence.” The Carranza representatives in the U.S. tried their best to pin suspicions on Sommerfeld. Carranza consul Beltrán in San Antonio told B.I. agent Beckham “… Sam Dreben, Sheldon Hotel, El Paso, and Felix Sommerfeld, New York City, were go-betweens for German interests and Francisco Villa.” According to the Carranza consulate in New York City, “Sommerfeld had told her [a woman without further description] in New York about 15 days ago that there would be intervention in a few days… Sommerfeld knew in advance about the Villa attack.” Bureau of Investigations Chief Bielaski took the Carrancista information seriously. He wired William Offley in New York City on March 14, “Legal representative Carranza Government wires Felix Sommerfeld assisting Villa and suggest he be shadowed and effects examined for incriminating evidence. Please give Summerfield [sic] activities immediate attention and make best possible effort to see what he is doing.” Interestingly, despite Chief Bielaski asking New York agents to locate Sommerfeld, they did not actually contact him in the Hotel Astor until May 5, 1916.

He may not have been there. The only evidence that Sommerfeld actually was in New York during the raid is a letter on Hotel Astor stationary he wrote to General Scott on March 10, 1916, in which he unequivocally condemned Villa’s attack. His actual whereabouts before and after the raid remain questionable. B.I. agents had interviewed the lawyer and Carranza lobbyist Sherburne Hopkins in Washington D.C. on February 28. He told the B.I. agents that the Catholic Church was financing an uprising against Carranza. He suggested for them to speak with Sommerfeld, who was “stopping at the Waldorf Hotel…” Sommerfeld had his office and regular living quarters in the Hotel Astor. Was he hiding from the prying eyes of those who knew where he regularly stayed? B.I. agents tried to locate Sommerfeld in New York at the end of April, but could not find him. Instead, agents along the Mexican border in April reported Sommerfeld to be “in Los Angeles under an assumed name and evidently in disguise… on the street in Los Angeles dressed somewhat roughly.” B.I. Agent Barnes in El Paso also reported him “here under assumed name,” and asked “is he wanted…?”He was not. Most likely, Sommerfeld did go to the border before the raid to help supply Villa with munitions and to canvas the situation for the German secret service. Plenty of B.I. reports point to Sommerfeld remaining Villa’s arms and munitions buyer with evidence of his purchases from merchants in Los Angeles, Boston, and New York abounding in the months before and after the attack on Columbus. Using a disguise and fake names, at the very least, demonstrated apprehension on the part of the German agent. Many historians have tried to find a definite link between Columbus and the German agent over the years, but Sommerfeld was much too skilled to leave a smoking gun behind.

The main theories of the motivation behind the raid all revolve around the fact that the Wilson administration had recognized Carranza and precipitated the violent reaction of Villa. Major Tompkins, the courageous cavalry officer who went after the raiders into Mexico, wrote a book about his experiences in which he also espoused this theory. He seconded most of the interventionist supporters in the Senate who blamed Wilson’s Mexico policy for the raid. All three theses, loot, vengeance, and German intrigue, contain what will ultimately prove to be a part of the historical truth. However, no one has yet fully explored the hard facts, the “how” in each of these theories. Villa certainly could have looked to Columbus as a source for loot, but there is no evidence or confirmation of this thesis. Vengeance against the American government proved itself a motivation, given Villa’s speeches, the letter to Zapata, and his actions in the prior months. The articles historian Katz wrote about the role of Leon Canova are the best argued and supported analyses on the topic.

The elephant in the room was the German strategy to tie American forces down at the Mexican border, and the German interest in the American military having to use arms and munitions for itself rather than selling them to Europe. German agents, before and after the attack, had played a significant role in precipitating and supporting the border conflagration. The challenge of this theory is to prove who did what and how. Sommerfeld’s mission to cause a war with Mexico and his role in helping convince Villa of an imminent danger to Mexico are well documented. The key to understanding the trigger of how German influence caused Villa to commence his attack lays within the background of the Enrile mission to Germany. Villa was outraged about the recognition of Carranza, he was even more mad at the Americans having actively participated in his downfall at Agua Prieta, maybe he had a grudge at Sam Ravel or, more likely the local bank that would not allow him to retrieve his deposits, but the trigger, the reason why he attacked on March 9 was the need to show Germany in this first battle of a new fight for supremacy in Mexico, that he was willing to act. For that he would receive German financial support, and remove Carranza from power.

I hope you enjoyed this series of blogs that traced the attack on Columbus as it was unfolding 100 years ago. I would appreciate very much, if you bought the book that contains this story in much greater detail and many other stories equally as fascinating as this. After all, Felix A. Sommerfeld was a spy who made James Bond look like an amateur. Please buy Felix A. Sommerfeld and the Mexican Front in the Great War on Amazon or right here as hardcover, paperback or e-book. And, of course, if you are in the neighborhood, hear me speak on Saturday right here in Columbus or next week in Albuquerque. For more information on these events, go to www.facebook.com/secretwarcouncil and look at the event calendar.