In early January 1915, one hundred years ago almost to the day, the German minister to Mexico, Heinrich von Eckhardt, dispatched the secret agent Arnold Krumm-Heller to Pancho Villa. The Imperial German government had decided to offer military advisers to the two revolutionary factions, and supplying them with arms and munitions from the U.S., while at the same time supporting Venustiano Carranza in his quest to consolidate his steady march to supremacy in Mexico. Fanning the flames of the revolution was supposed to keep the United States government focused on Mexico rather than Europe where Germany fought a desperate war on two fronts.

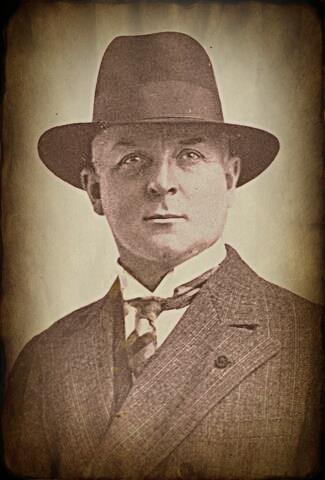

Arnold Krumm-Heller: Medical Doctor, Revolutionary, German Spy

Villa knew Krumm-Heller, who had been President Francisco Madero's personal doctor and spiritual adviser in 1911 and 1912. After Madero's demise in the Decena Tragica, Krumm-Heller joined the Carranza camp, which at that time included Villa's faction. However, in the spring of 1915 serious rifts had developed between Carranza and Villa. As a result, Villa saw Krumm-Heller's entreaty with more than just casual suspicion. Had Carranza dispatched Krumm-Heller as a military spy? Villa not only rejected him, but asked the messenger who submitted Krumm-Heller’s offer to tell him, “I give him [Krumm-Heller] 24 hours to get out of my country. If he is found here after that I will have him shot.”

The German agent took his military advisers and joined the forces of Alvaro Obregon, a loyal Carranza general. Within months, the German instructors taught Obregon the newest techniques from the European war. Frontal attack, being the mainstay of Villa's military tactics, could be stopped with elaborate trenches, the use of barbed wire and carefully placed machine gun positions. The first major encounter between Villa and Obregon's forces occurred at Celaya in April 1915. Obregon and his advisers had carefully chosen the battlefield and constructed an impenetrable bulwark against frontal cavalry assaults. Against the advice of Felipe Angeles, his most important military strategist and general, Villa sent wave after wave of cavalry against the entrenched forces of Obregon. After brutal fighting and heavy casualties, running low on ammunition, Villa retreated. Two weeks later, after resupplying and regrouping, the two armies clashed again. In desperate fighting, Obregon's forces managed to hold back the attaching Villistas.

Throughout both battles, Krumm-Heller and his German military staff observed the battlefield from a tent on high ground and gave Obregon tactical advice. However, early in the second battle artillery shrapnel severed Obregon's right arm. Laying in a tent in agony with his staff desperately trying to prevent their commander from committing suicide, Obregon's injury threatened to unravel the Constitutionalist lines. A few days after the battle, a reporter of the Hearst newspaper empire handed a report from Captain Juan Rosales, a Carranzista living in El Paso, to the Bureau of Investigation:

“General Obregón had his arm shot off early in the fifth, and then Krum [sic] Heller took charge. He had five German officers with him. None of them went into the field, but as every Mexican officer had been instructed by Obregón to obey Heller, he and his Germans sat in a little tent away from the firing line and made maps. On several occasions they rode out to hills and looked at everything through their field glasses. Then they would return to their tent. I was attached to Col. Heller’s staff. Late that night Col. Heller sent for every Carranzista officer. Some of them regarded them as foolish and threatened to disobey, but Heller again produced an order signed by General Obregón commanding every Carranzista officer to obey him (Heller) [.] That settled the matter and the fight soon began. It did not last long. Villa was whipped and then retreated. Heller gave more instructions and our army advanced. Villas [sic] was whipped again and retreated. Heller again followed him and whipped him again. This was the end if Villa’s army.”

Alvaro Obregon after the Second Battle of Celaya

Krumm-Heller remained with Carranza in Mexico until 1916, then became military attache for Mexico in Berlin. After Celaya, Villa's chief military adviser Felipe Angeles left for the United States. Felix Sommerfeld, a German naval intelligence agent on Villa's staff funneled German funds to Villa to purchase more arms and munitions though 1915. By the fall, Villa's army, battered and decimated, fought a last stand in Sonora which it lost. Villa took to the hills in December 1915. The proud Division of the North, at one time counting over 40,000 men, disbanded.

More on the career of Arnold Krumm-Heller at the 2015 Conference on Mariano Azuela and the Novel of the Mexican Revolution at California State University May 15 to May 16.