On February 19th 1915, one-and-a-half months before war bonds hit the market and three weeks before the Foreign Office approved the sabotage campaign in the United States, the Deutsche Bank deposited $210,000 ($4.4 Million in today’s value) with G. Amsinck and Co. One week later another $790,000 ($16.6 Million in today’s value) appeared as a deposit for the Deutsche Bank. The director of the Deutsche Bank in the United States was Hugo Schmidt. He proved to be an expert in finding ways around the tight control of financial transactions through Britain. Virtually all international financial transactions in one way or another passed through London. British authorities made sure that German transactions did not make it any further. Through dummy accounts, fake bank connections, straw men from neutral countries, especially those in Latin America, Schmidt became the essential lifeline to the German officials in the United States. An assistant, Frederico Stallforth, who had lots of international connections and plenty of financial savvy worked at his side.

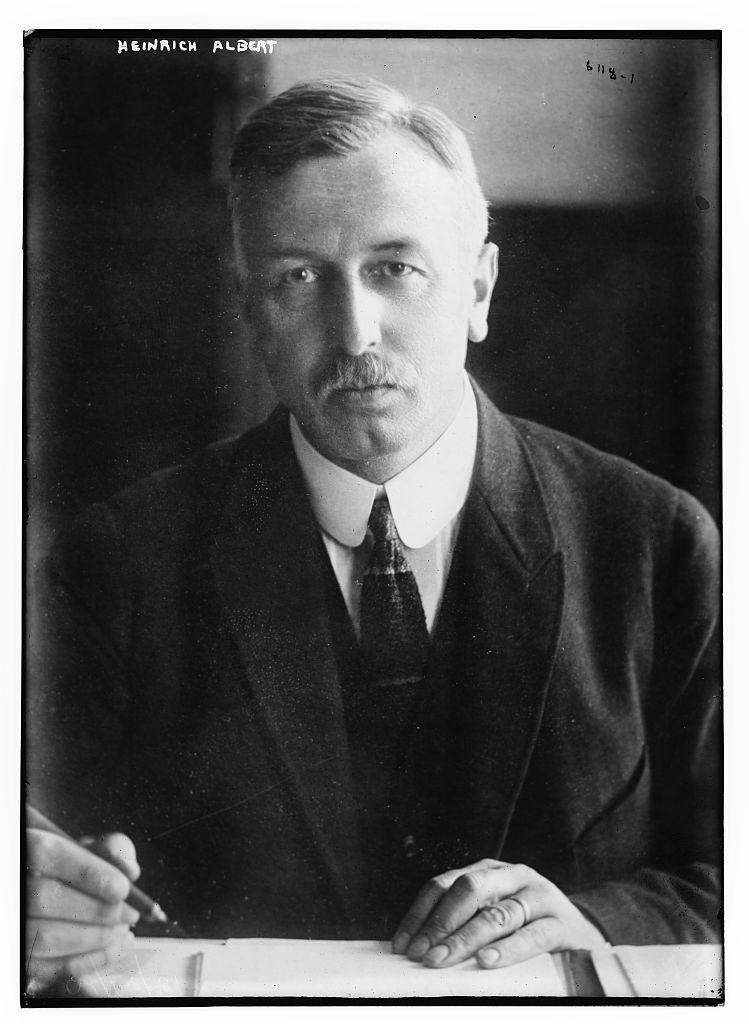

Heinrich F. Albert in his office in New York in 1915

The one million dollars that Albert received in February 1915 were not coded in his ledgers as credits for shipping supplies to Germany as part of the blockade running operation. These million dollars came from the Imperial War Department with the express purpose of financing the sabotage order that the New York team had received on January 24th. Proceeds from the sale of war bonds further filled the coffers in April 1915. Within weeks of receiving the revenue from the war bonds, Albert and German Ambassador in the U.S., Count Bernstorff, opened dozens of new accounts all over the country, ostensibly to have funds where after nine months the bonds would eventually be redeemed. Rather than cashing the coupons, these regionally distributed bond proceeds actually funded clandestine operations.

Franz von Papen in 1915 on his way home after he had been expelled from the U.S.

The collection and dissemination of intelligence as well as the dispatch and payment of secret agents occurred at the War Intelligence Office at 60 Wall Street, the office of Franz von Papen and his assistant Wolf von Igel in New York. Every day, German sympathizers and agents sent reports to von Papen’s office. This raw intelligence detailed factories involved in producing supplies for the Allies, named sympathizers who could be approached inside those businesses, as well as all kinds of plans, from inventions to bomb designs, to setting fires, to sabotaging manufacturing facilities. The acting German Military Attaché Wolf von Igel and other officials had destroyed many of these telegrams and letters as American investigators tried to search the premises of the German operation in New York between 1915 and 1917. However, some examples have been preserved that show the amount of intelligence von Papen had at his disposal to decide what to attack, how, and when. For example, he filed one of his bi-weekly intelligence reports copied to his superiors in Berlin, as well as those of Boy-Ed and Albert on February 11th 1915. The New York team was then still planning to corner the munitions market in the U.S. However, in view of the earlier sabotage order, which might or might not have arrived in the U.S. by the second week of February, von Papen seems to allude to potential sabotage targets using words like “there come into consideration...”

… Bethlehem Steel Works are shipping on the steamer Transylvania 2 heavy naval guns, 16” caliber, which are said to represent a part of a large order… The entire order is estimated at 200 guns. The Savage Arms Co. delivers weekly about 50 Lewis machine guns… Westinghouse Electric Co. … got contracts for 125,000 shrapnel, the J.W. Bill Co. Projectile Works (shrapnel), the Western Cartridge Co., Alton, Ill. (cartridge shells) and the Bridgeport Brass Co. (cartridge shells). Machines for making shrapnel are furnished… by Gisholt Machine Co. and the Steinle Turret Co… For infantry ammunition there come into consideration [underline by author], besides those already reported, the Western Cartridge Co., Alton, Ill (caliber 30-20 and 7m.m. cartridge shells) and the Bridgeport Brass Co. (cartridges, shells and 50 million copper bullets for French machine guns [)]. The Curtis Flying Machine Co. is supplying 400 flying machines to England… These machines are equipped… with the only recently invented gyroscope of the Sperry Gyroscope Co… The well-known parts are produced by the Union Twist Drill Co. and the Union Twist Reel Co…It is rumored that the allies are ready to take as many as 1,000,000 daily.

The shipments of horses and war automobiles continue in increased degree. The Ford Mfg. Co. has received an order for 40,000 vehicles… the factory can produce about 1,000 a day.

The Locomobile Co. of America makes heavy freight automobiles and even sends its trained chauffeurs along to France with the autos… 35 heavy guns were sent by the Bethlehem Co. to Vancouver, to be shipped from there on the steamer Tambov of the Russian volunteer fleet to Vladivostok… The same factory furnished also the ammunition for this gun, and a report is before me that one train took 15 car loads of this. The steamer Tambov is said also to be taking powder from the DuPont Powder Co., also dynamite…

The Baldwin Locomotive Works shipped on the steamer Indradeo twenty-five locomotives to Vladivostoc.

Automobiles are shipped on every steamer leaving Vancouver for Vladivostok, and the Case Automobile Co. is specially to be mentioned here… Signed Papen

The financial control of the intelligence operation rested with Heinrich Albert’s office around the corner in the Hamburg-America building on 45 Broadway. Any sum over $10,000 had to be approved by Albert. The German agent and creator of the fire bombs that destroyed American factories and Allied ships, Walter Scheele, told investigators in March 1918, “In all matters of policy, it is stated that Dr. Albert ranked Bernstorff, Von Papen [sic] and Boy-Ed by many points. They all had to go to him. There was no plot or scheme which was unknown to him. As a result, literally nothing of import went on without Albert’s approval or at least his knowledge.”

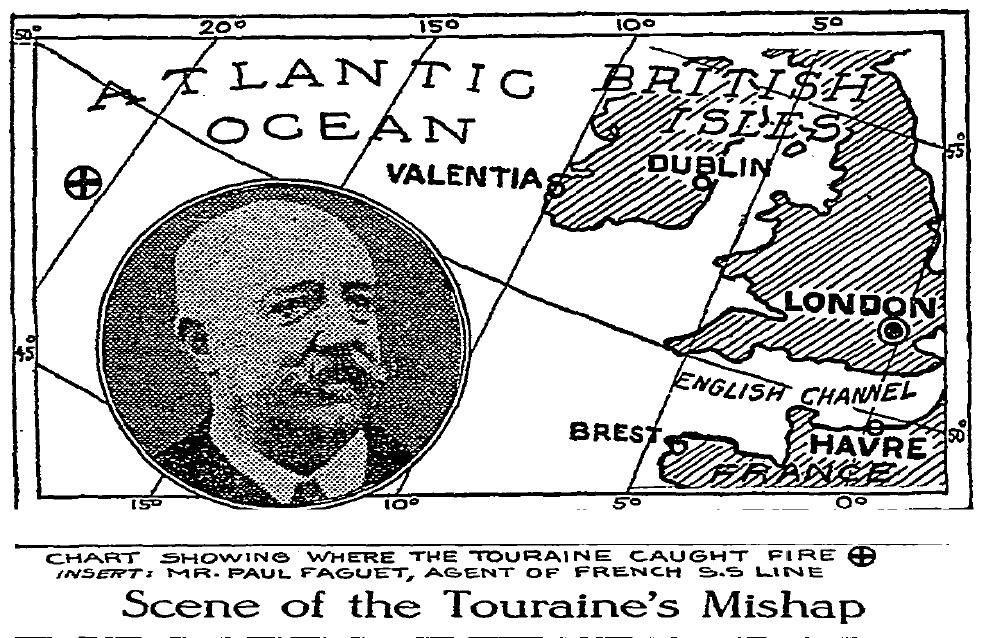

Four weeks after Albert received the first funds to start the sabotage campaign, on March 17th, von Papen reported in code to his superiors in Germany, “Regrettably steamer [SS La] Touraine has arrived unharmed with ammunition and 335 machine guns.” Von Papen was being facetious. She had indeed sailed on February 27th from New York to Le Havre, France, and caught on fire five hundred miles off the coast of Ireland on March 6th. The New York Times reported the next day, “only the barest facts of the disaster on the Touraine are known, and there is no hint of the cause of the fire on board the vessel… A message from Queenstown said that the fire on the Touraine was ‘fierce.’” The fire had broken out in two separate cargo areas. French authorities immediately suspected foul play. After a thorough investigation authorities identified a suspect who, as it turned out, had not caused the fire. Either way, von Papen’s superiors now had evidence that the sabotage campaign they had ordered was in full swing. If it had been Scheele’s work, the bomb maker had scored a first, documented success. Of the eighty-four passengers nobody was hurt. However, the cargo was ruined. The Touraine was the first casualty of what would become a staggering crisis for the U.S.: Over fifty freighters damaged or destroyed, three U.S. warships destroyed in dry dock, sky rocketing insurance premiums, billions of dollars in losses from factory fires, labor strikes across the rust belt, and hundreds of casualties not the least 128 American passengers on the Lusitania. Except for the Lusitania sinking, Heinrich Albert financed every aspect of the sabotage campaign that year.