Die Revolution hatte still und unbemerkt begonnen. Bis zurück ins Jahr 1906 hatten nur hier und da kurze Strohfeuer des Unmuts den politischen Horizont des Landes für Augenblicke erhellt, die jedoch gleich wieder in der trügerischen Stille unter Porfirio Diaz’ eiserner Hand erstickt wurden. Da der alternde Diktator und sein auserwählter Beraterstab der „Cientificos“ es bis zuletzt verweigerten, die Übergabe der Macht in einem geordneten Rahmen zu planen, brach die Gewalt im Herbst des Jahres 1910 los. Zu dieser Zeit fegte ein regelrechter Sturm aus finanziellen Krisen und Naturkatastrophen über das Land. Zudem gab es eine junge Generation mittelständischer Mexikaner, die keinerlei politisches Gehör fand. Für viele Zeitzeugen kam Diaz’ abrupter Machtverlust überraschend. Madero trat als gemäßigter Vertreter einer breiten Koalition aus Unternehmern, Grundbesitzern, Industriellen, dem Militär, der Arbeiterschaft und der Bauern auf. Sein Ziel war die Errichtung eines demokratischen Systems, in dem jeder Mexikaner politisch vertreten war, sowie eines unabhängigen Rechtssystems, das die Grundlage für Landreformen bilden und eine Entwicklung hin zu sozialer Gerechtigkeit auf den Weg bringen sollte. Dass diese allmählichen Reformen den Durst nach einem besseren Leben von siebzehn Millionen Mexikanern zu stillen vermochten, wurde in den hitzigen Tagen des Mai 1911 nur von wenigen scharfen Beobachtern bezweifelt. Tatsächlich sollte es angesichts der Vielzahl an verschiedensten Interessengruppen, die Madero mobilisiert hatte, noch weitere neun Jahre dauern und über eine Million Leben kosten, bis ein neuer Gesellschaftsvertrag zustande kommen sollte, dessen letzte Paragraphen erst in den 1940er Jahren fertiggestellt wurden. Die Revolution, die Madero während seines Triumphzugs durch Mexico City für abgeschlossen hielt, hatte in Wahrheit erst begonnen.

Niemand in der Menge oder gar im engen Vertrauenskreis um Madero hatte auch nur die leiseste Ahnung davon, welche Rolle Sommerfeld über die kommenden zehn Jahre in ihrer Revolution spielen sollte. Maderos Sieg über den Diktator wurde größtenteils auf dem Schlachtfeld, aber auch in einer Suite des New Yorker Astor Hotels und an weiteren Verhandlungsschauplätzen in Mexiko und den Vereinigten Staaten ausgefochten. Die Absetzung des alten Diktators sollte lediglich eine gewonnene Schlacht in einem lange währenden Krieg darstellen, in dem Felix Sommerfeld nicht zufällig, sondern durch die gezielte Beeinflussung der Geschehnisse eine Schlüsselrolle zukommen sollte. Ohne das Wissen seiner Mitstreiter hatte Sommerfeld spätestens seit 1908 für den deutschen Marinenachrichtendienst gearbeitet, und deutsche Agenten hatten ihn in den Kreis um den zukünftigen Präsidenten eingeschleust. Von dort aus gelang Sommerfeld der Aufstieg zum höchsten Posten, den ein deutscher Spion in der mexikanischen Regierung jemals bekleidete. Während seiner Arbeit für Präsident Madero fungierte der deutsche Heeresreservist, wohl mit dessen stillschweigender Zustimmung, als Verbindungsmann des deutschen Botschafters in Mexiko, Konteradmiral Paul von Hintze, und versorgte diesen mit wertvollen Informationen über Mexiko, Europa und die Vereinigten Staaten. Durch Sommerfelds Einsatz war es Deutschland möglich, seine außenpolitischen Bestrebungen auf Madero und dessen Nachfolger Huerta zu konzentrieren. Kein anderer Ausländer hatte in der Mexikanischen Revolution mehr Einfluss und Macht. Ausgehend von seinem Posten als Sicherheitschef nahm sich Sommerfeld bald der Gründung und Befehligung des Mexikanischen Geheimdienstes an. Unter seiner Schirmherrschaft entwickelte sich die größte ausländische Geheimdienstorganisation, die jemals auf US-amerikanischem Boden operierte, bald zu einer Waffe, die Maderos Feinde terrorisierte und dezimierte. Seine Organisation stellte sich als so effektiv heraus, dass die US-Regierung später große Teile davon in das „Bureau of Investigation“ übernahm.

Sommerfeld konnte den Untergang von Francisco Madero, dem Revolutionsführer, den er so schätzte, nicht verhindern. Der Oberbefehlshaber der Armee, General Victoriano Huerta, riss die Präsidentschaft 1913 an sich und ordnete die Ermordung Maderos in einem blutigen Staatsstreich an. Sommerfeld entkam nur knapp Gefängnis und Erschießungskommando und reaktivierte seine Geheimdienstorganisation entlang der US-amerikanischen Grenze für den Kampf gegen den Putschisten Huerta.

Der folgende Krieg um die Vertreibung des reaktionären Machthabers aus Mexikos Präsidentenpalast wütete nicht nur auf dem Schlachtfeld, wo hundert tausende Mexikaner unter der Führung von Venustiano Carranza, Emiliano Zapata, Alvaro Obregon und Pancho Villa für die zweite soziale Revolution des Jahrhunderts kämpften, die Entscheidung über Sieg oder Niederlage stand und fiel besonders auch mit der Versorgung und Finanzierung der revolutionären Truppen. Sommerfeld wurde dank seiner Beziehungen zu Deutschland und den USA zum Dreh- und Angelpunkt dieser Versorgungskette. In bisher undenkbarem Ausmaß schmuggelte seine Organisation Waffen und Munition und belieferte damit die Rebellen – gleichzeitig führten seine Beziehungen bis in die obersten Kreise der Regierungen Deutschlands und Amerikas dazu, dass Huerta von dieser Seite weder Kredite, noch Waffenlieferungen zuteilwurden. Die Interessen des deutschen Agenten, der an der Seite der mexikanischen Revolutionsbewegung agierte, überschnitten sich mit den Plänen der deutschen und amerikanischen Regierungen. So ist es zwar verwunderlich, aber keineswegs unlogisch, dass die Amerikaner uneingeschränkt mit Sommerfeld kooperierten und dessen zahlreiche offenkundige Übertretungen US-amerikanischen Rechts schweigend billigten. Natürlich kann man Sommerfeld den Sieg über den Mann, der Maderos Tod angeordnet hatte, nicht gänzlich allein zuschreiben, sein Anteil am Sturz Huertas war jedoch maßgeblich.

Dieses Buch setzt sich nicht zum Ziel, eine vollständige Analyse über Hintergründe und Verlauf der Mexikanischen Revolution anzustellen. Vielmehr erzählen die folgenden Seiten eine faszinierende und in Vergessenheit geratene Geschichte, die nur einen Bruchteil des großen Ganzen darstellt. Es existieren zahlreiche große Werke über die Mexikanische Revolution und viele davon wurden auch als Quellen für dieses Buch herangezogen. Erhöbe dieses Buch den Anspruch einer allumfassenden Abhandlung, so täte dessen enger Fokus einem ganzen Volk, das sich gegen die Unterjochung einer Diktatur aufgelehnt hat und für soziale Gerechtigkeit in den Kampf gezogen ist, sicher großes Unrecht. Jedoch zeichnete sich bereits im Vorfeld der Revolution ein gewisses Element außenpolitischer Machenschaften ab, welches einen erheblichen Einfluss auf ihren Verlauf und letztlich ihren Ausgang hatte. Es waren Investitionen aus dem Ausland, die zu sozialer Unzufriedenheit und der politischen Entmündigung des mexikanischen Volkes führten und so zum Teil den Boden bestellten, auf dem die Hoffnungen der breiten Masse zu keimen begannen. Als der Bürgerkrieg durch Madero entfesselt wurde, taten international agierende Banken und Unternehmen, unterstützt durch ihre Regierungen, ganz klar ihr Bestes, um den Lauf der Dinge zu ihrem eigenen Vorteil zu beeinflussen und ihre Mitarbeiter und ihr Kapital zu schützen. Fremde Regierungen versuchten immer wieder, das Rad der mexikanischen Geschichte je nach ihren Bedürfnissen entweder zu beschleunigen, oder aber zurückzudrehen. Felix A. Sommerfeld war sicher nicht der einzige Geheimagent, der in Mexiko tätig war. Welche Maßstäbe man auch anlegt, so war er jedoch mit Sicherheit der einflussreichste und, wenn auch der am wenigsten verstandene, doch der effektivste von ihnen, da er es vermochte, die Interessen Mexikos, Deutschlands und der USA so zu verbinden, dass deren Aktionen letztlich stets seinem eigenen Zweck dienten. Diese beeindruckende Fähigkeit weckte bei zahlreichen Forschern Zweifel an seinen tatsächlichen Beweggründen, und nicht selten wurde er als Doppel- oder sogar Dreifach-Agent bezeichnet. Doch weit gefehlt – dieser deutsche Agent verkaufte Informationen und Gefallen, nicht jedoch seine Integrität.

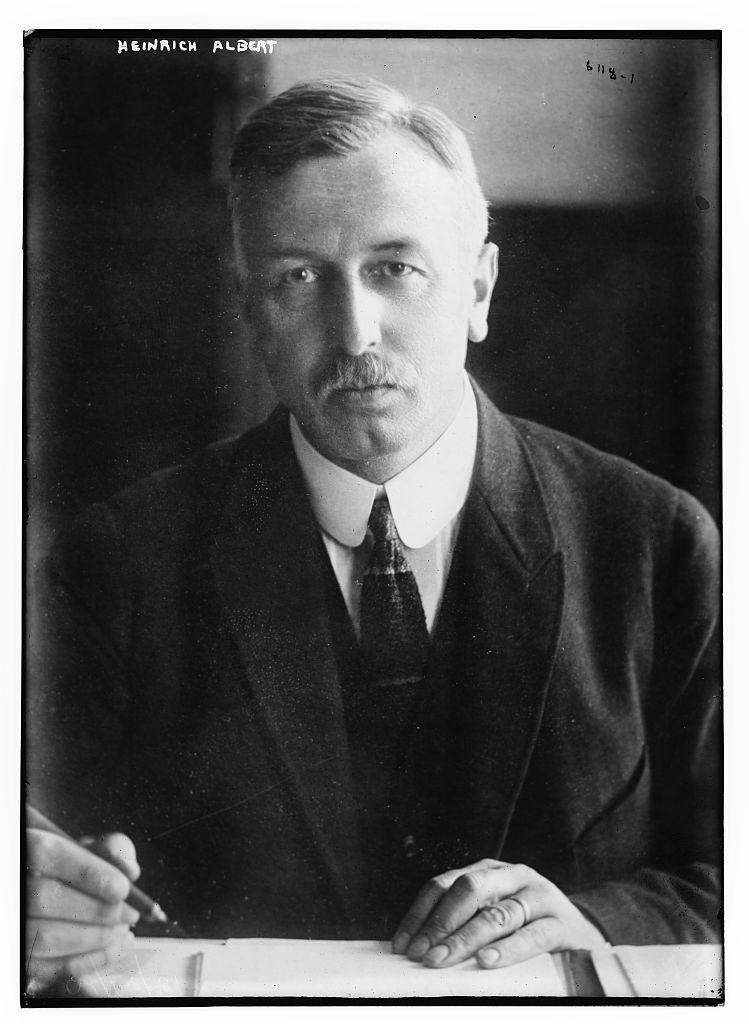

Sommerfeld scharte eine Gruppe von Mitstreitern um sich, die ihm während der Revolution und auch später zur Seite standen, als Mexiko Schauplatz des Ersten Weltkrieges wurde. Keiner seiner Mitstreiter schien sich jedoch darüber im Klaren zu sein, unter wessen Befehl der Deutsche tatsächlich stand. Wie alle großen Spionagekünstler entschied Sommerfeld darüber, wer in seinem Stück welche Rolle übernehmen sollte und er versorgte seine Akteure immer nur mit den Informationen, die er für notwendig hielt. Der Rechtsanwalt, Lobbyist und politische Strippenzieher Sherburne G. Hopkins wurde zu Sommerfelds Hauptkontakt in den USA und von 1911 bis 1914 sein Vorgesetzter. Durch ihn erlangte Sommerfeld Zugang zu den innersten Kreisen der Regierung um Präsident Wilson. So wurde Wilsons Generalstabschef, General Hugh Lenox Scott, zu Sommerfelds Freund, Kriegsminister Lindley Garrison empfing ihn zum Tee, wann immer er nach Washington kam und die Senatoren William Alden Smith und Albert Bacon Fall luden ihn ein, vor dem Sonderausschuss für Mexiko zu sprechen. Durch Hopkins‘ Einfluss öffnete sich für Sommerfeld auch in New Yorks Finanzkreisen so manche Tür. Als Anwalt und Lobbyist des Industriellen Charles Ranlet Flint und des Öl-Tycoons Henry Clay Pierce platzierte Hopkins Sommerfeld als primäre Anlaufstelle für alle amerikanischen Unternehmer, die mit den Regierungen Madero, Carranza und Villa Kontakt aufnehmen wollten. Von Zeit zu Zeit agierte Sommerfeld sogar im persönlichen Auftrag von Präsident Wilson und der bunten Schar von Amateurdiplomaten, denen man im Weißen Haus vertraute. Die Kontrolle über entscheidende Teile des Informationsflusses, die Sommerfeld dank seiner Stellung zur amerikanischen Regierung ausüben konnte, ermöglichte ihm die gezielte Manipulation der amerikanischen Außenpolitik für seine eigenen Zwecke.

Von allen Menschen, die Sommerfeld in seinem Leben begleiteten, blieb Frederico Stallforth am längsten an seiner Seite. Stallforths Eltern waren Deutsche, er selbst jedoch im Norden Mexikos geboren, und so ist sein Leben vor und während der Revolution für die Situation ausländischer Geschäftsleute und Auswanderer in Mexiko auf vielerlei Art und Weise beispielhaft. Als Minenbesitzer und Bankier in seiner Heimatstadt Hidalgo del Parral in Chihuahua, hatten er und seine Familie besonders schwer unter den Auswirkungen der Revolution zu leiden. Chihuahua war während des größten Teils der Revolution Hauptschauplatz der Auseinandersetzungen an einer sich ständig bewegenden Front, und obwohl Stallforth (durch seinen Freund Sommerfeld) Kontakte zur mexikanischen und amerikanischen Regierung, der Wall Street und zu wirtschaftlichen und diplomatischen Kreisen in Deutschland unterhielt, schmolzen sein Familienvermögen und sein in Mexiko investiertes Kapital unter der glühenden Hitze der Kämpfe dahin. Dies war größtenteils nicht sein eigener Fehler, vielmehr waren er und seine Familie bedingt durch die wirtschaftliche und soziale Situation in der Zeit vor der Revolution wie Geiseln in Mexiko gefangen. Während der Untergang des Familienunternehmens für die meisten Ausländer in Mexiko bereits das Ende bedeutete, fing Stallforths Karriere damit erst an. Mittellos und desillusioniert schloss er sich Sommerfeld in New York an und wurde zu einem der einflussreichsten deutschen Agenten in den Vereinigten Staaten. Wie auch im Fall von Felix A. Sommerfeld ist seine Rolle in der Geschichtsschreibung zu großen Teilen unklar.

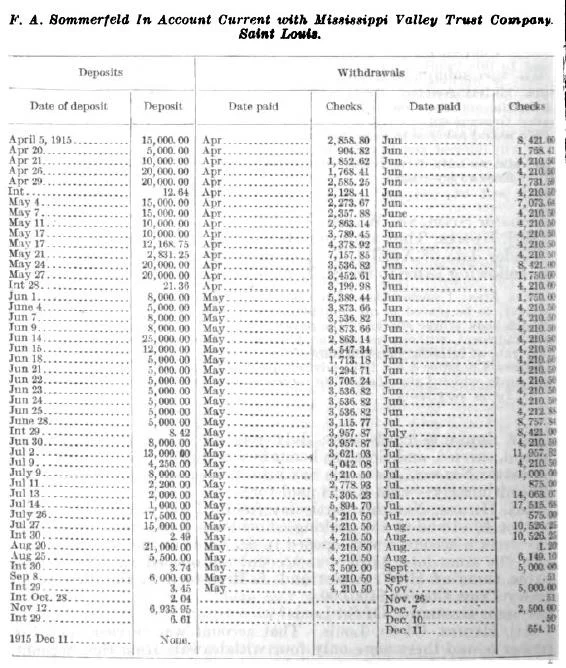

Der Name Sommerfeld erscheint in fast jeder Arbeit zur Mexikanischen Revolution. Die Historiker Harris und Sadler bemerkten, dass sich „… Sommerfeld durch die Mexikanische Revolution bewegte wie ein Geist.“ Während Harris und Sadler die einzigen Historiker sind, die Sommerfeld den Titel des „Meisterspions“ zukommen lassen, schreiben ihm andere wie beispielsweise Friedrich Katz und Michael Meyer eine enigmatische und eher unklare Rolle zu. Wieder andere, wie beispielsweise Jim Tuck, bezeichnen ihn als „Hochstapler“, „Abenteurer“, „zwielichte Gestalt“ und „Doppelagent.“ Um letztlich zu einem dreidimensionalen Bild von Sommerfeld und den Zeiten, in denen er agierte, zu gelangen, stellt dieses Buch Sommerfelds und Stallforths Aussagen vor dem US-Justizministerium und Aufzeichnungen aus privaten und öffentlichen Sammlungen gegenüber. Die Akten des Justizministeriums und des FBI zu Mexiko und Deutschland von 1908 bis 1922 sind seit Jahren freigegeben und für Historiker einzusehen, ebenso die Akten der Schadenskommision, des US-Marinegeheimdienstes, der Nachrichtendienstabteilung der U.S. Army und umfangreiche Sammlungen des US-Staatsarchivs unter dem Titel „Captured German Documents“ (i.e. „Beschlagnahmte Deutsche Dokumente“). Zudem sind die persönlichen Aufzeichnungen von Pancho Villas Finanzvertreter Lazaro De La Garza und seines Hauptstrategen und Gouverneurs von Chihuahua, Silvestre Terrazas, von General Hugh Lenox Scott, Präsident Woodrow Wilson und seinem Kabinett, sowie die des Glücksritters Emil Holmdahl einzusehen. Bisher unbekannt sind die persönlichen Aufzeichnungen Frederico Stallforths. Dieses Buch ist das Ergebnis eines detaillierten Vergleichs amerikanischer, mexikanischer und deutscher Archivinformationen. Nicht zugänglich sind die Akten des deutschen Geheimdienstes und des deutschen Militärgeheimdienstes, da diese 1945 den Flammen des Zweiten Weltkriegs zum Opfer fielen. Auch Felix Sommerfelds persönliche Aufzeichnungen sind bisher noch nicht aufgefunden worden.

Trotz der zentralen Rolle, die Sommerfeld in der Mexikanischen Revolution gespielt hat, und obwohl man in den historischen Aufzeichnungen häufig auf Berichte über sein Handeln stößt, verstand es der deutsche Agent, seine Spuren zu verwischen. Weder seine Zeitgenossen, noch die Historiker der letzten hundert Jahre haben es geschafft, den geheimen Werdegang Sommerfelds aufzudecken, der die Heldentaten eines James Bond wie ein Kinderspiel aussehen lässt. Als Meisterspion in der Mexikanischen Revolution und während des ersten Weltkrieges bleibt Sommerfeld für seine Zeitgenossen und auch für Historiker bis heute verborgen im Schatten der Öffentlichkeit.